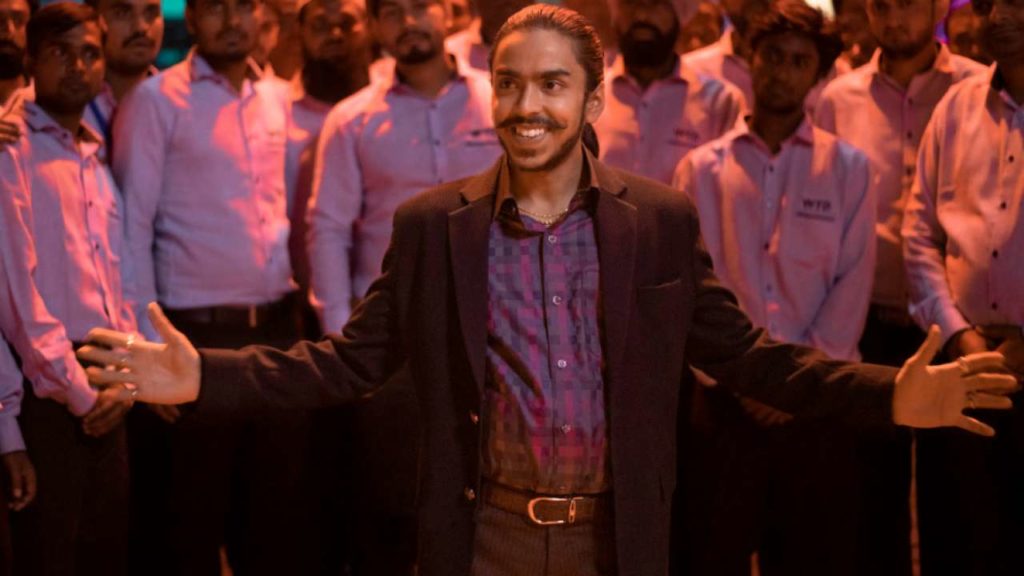

Ramin Bahrani’s The White Tiger (2021) is a cinematic adaptation of Arvind Adiga’s 2008 Booker Prize winning novel of the same name. The story traces the journey of Balram Halwai, played by Adarsh Gourav, born of a low-caste, impoverished family in Bihar’s Laxmangarh, from a servant oppressed by his socio-economic status to that of a successful entrepreneur.

Since the film’s release on Netflix on 22nd January, several critics have compared it to the famed Oscar-winning Slumdog Millionaire (2008), and emphasized on how this film takes the route of ‘poverty porn’; defined as the exploitation of poor living conditions to generate sympathy, which some view as a growing genre in Hollywood films.

The choice to stick to the original language of the novel, English, has mostly received negative reviews. People have been quick to highlight how the production targets a niche audience, predominantly an English-speaking cosmopolitan local population, in addition to the global audience, at the cost of a more realistic representation of people in rural and suburban India, and authentic every day conversations.

The constant voice-over narration employed in the film has also received a mixed response. While some perceive it as an annoying intrusion, a few others feel it accurately captures the essence of the novel.

The film closely resembles a social commentary, but it does not brazenly critique any social evil or crime, but merely offers glimpses of it in passing. One exception to this rule, is the class divide, which overshadows other inequalities such as caste and religion. A few instances do depict these but fall short of creating an impact.

Balram works as a driver for Pinky (Priyanka Chopra Jonas) and Ashok (Rajkumar Rao), the rich couple who serve as his ladder to wealth. His relationship with them can be summed up in this rhetorical question, “Do we loathe our masters behind a façade of love, or do we love them behind a façade of loathing?”.

He says there are only two castes, “Men with big bellies, and men with small bellies. And only two destinies: eat — or get eaten up”. Social mobility is achieved through killing; realistic enough, but stereotypical at the same time.

Two metaphors rule the film, that of the poor masses as roosters in a coop, and that equating Balram, the one who dares to dream and rise out of his marginalized identity, to a white tiger, a creature that is born once a generation, but an animal nevertheless.

Betrayal and corruption; economic as well as moral, pervade all classes, and ‘survival of the fittest’ is a constant presence. This film and Bong Joon-Ho’s Parasite (2019) are similar in their representations of the abysmal life and aspirations of the poor, but they part ways when it comes to capitalism, which the latter sternly critiques, and in the former it is treated as an agency of redemption in Neo-liberal India while not discounting the malice in this particular case.