With reduction in land productivity due to increasing pressure on over-burdened land resource and climate change, India has planned to make a significant shift over to its waters, an abundant yet less-utilized treasure.

When it comes to water usage, people of India have never been so demanding. We revere our waters and our histories boast of our devotional fondness towards such a blessing. Our North Indian plains are engraved with a mesh of such river system. In the same manner, Our Southern Peninsular plateau caters to many such beautiful rivers, paving their ways howsoever into the respective Seas.

There may be areas like the splendid North East and Nepal-Bihar border that faces extravagant floods each year, pre as well as during Monsoon. And we also host areas like Bundelkhand, Vidarbha or even arid regions of Rajasthan, where there is complete dearth of water, be it for Irrigation, drinking purposes or for meeting daily ends and means.

At times this available resource may save our frail lives or they may even work to take unintended lives.

Getting fresh and clean water to consume in India is still aspirational for many. According to Niti Aayog’s Composite water Index, India is facing its ‘worst’ water crisis in history and that the upcoming demand for potable water will out rule its supply by 2030 if sufficient steps are not taken.

Other threats include a high to extreme water stress to be faced by 600 million Indians and about 2,00,000 people to die every year due to inadequate access to safe water. Twenty-one Indian cities like the capital Delhi, Bengaluru, Chennai and Hyderabad will run out of groundwater by 2020 bringing 100 million people on the brink of water crisis.

On similar lines, WASH report by UNICEF explains the repercussions of water scarcity on health, economy and sustainability.

Therefore, it has become a necessity to undertake balancing and management of this precious resource. Dams, canals alone cannot make things right.

Although traditional water conservation methods like Kuls, Johads, Ahar, Drip Bamboo Irrigation system etc. all worked expectantly for the clean water availability but equitable access to water as guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution could not be achieved.

How it all began?

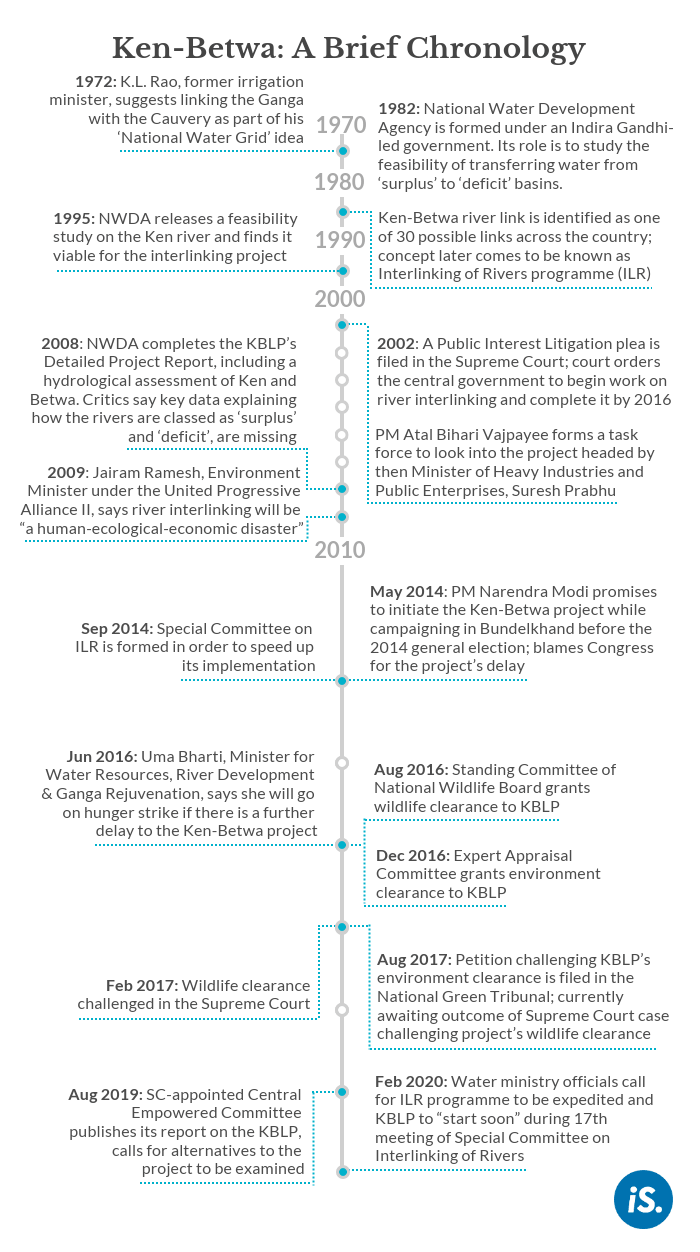

For trade purposes, British Colonialist and Engineer Arthur Cotton first mooted the concept of interlinking of rivers to meet the aims of providing adequate water to a population without compromising with the needs of the others i.e. surplus waters to be diverted to deficit areas.

The idea of linking the rivers of India found shape in the thoughts of Visveswarya, the legendary Engineer. This idea was further accentuated by Dr K.L. Rao who dauntingly proposed “National Water Grid” as a core solution to all such water problems.

Other needs for such Interlinking:

Apart from drinking water shortage, Droughts and floods, there are other embedded reasons too:

- Burgeoning population and inadequate food security.

2. Disaster Management can be done via proper utilization of excess waters.

3. Important for long term sustainable productivity of these river basins.

4. Helps in transporting excess salt in water through mixing and diffusing of salts that is needed to sustain aquatic ecosystems.

5. As an alternative mode of transport; for logistics and daily freight movement. This may serve as a cleaner, low carbon footprint form of transport infrastructure, particularly for ores and food grains. It is to note that National waterways have been started for such classified movement.

What is the National plan for Interlinking rivers?

The National perspective plan as envisioned by the Government includes 150 million acre feet (MAF) (185 billion cubic metres) of water storage along with building inter-links across the country.

It has two components attached to it, i.e. to develop Himalayan rivers(of the rivers linked to Ganga-Brahmaputra basin) and Peninsular rivers(deccan perennial rivers).

Ken-Betwa Link as Country’s first river interlinking project:

Although On 16 September 2015, Krishna and Godavari rivers were first linked but it doesn’t hold as a true river interlinking as it is just a small lift irrigation with few lines of pipes.

Recently, Chief Ministers of Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh have signed a mutual historic agreement to implement the Ken Betwa Link Project (KBLP).

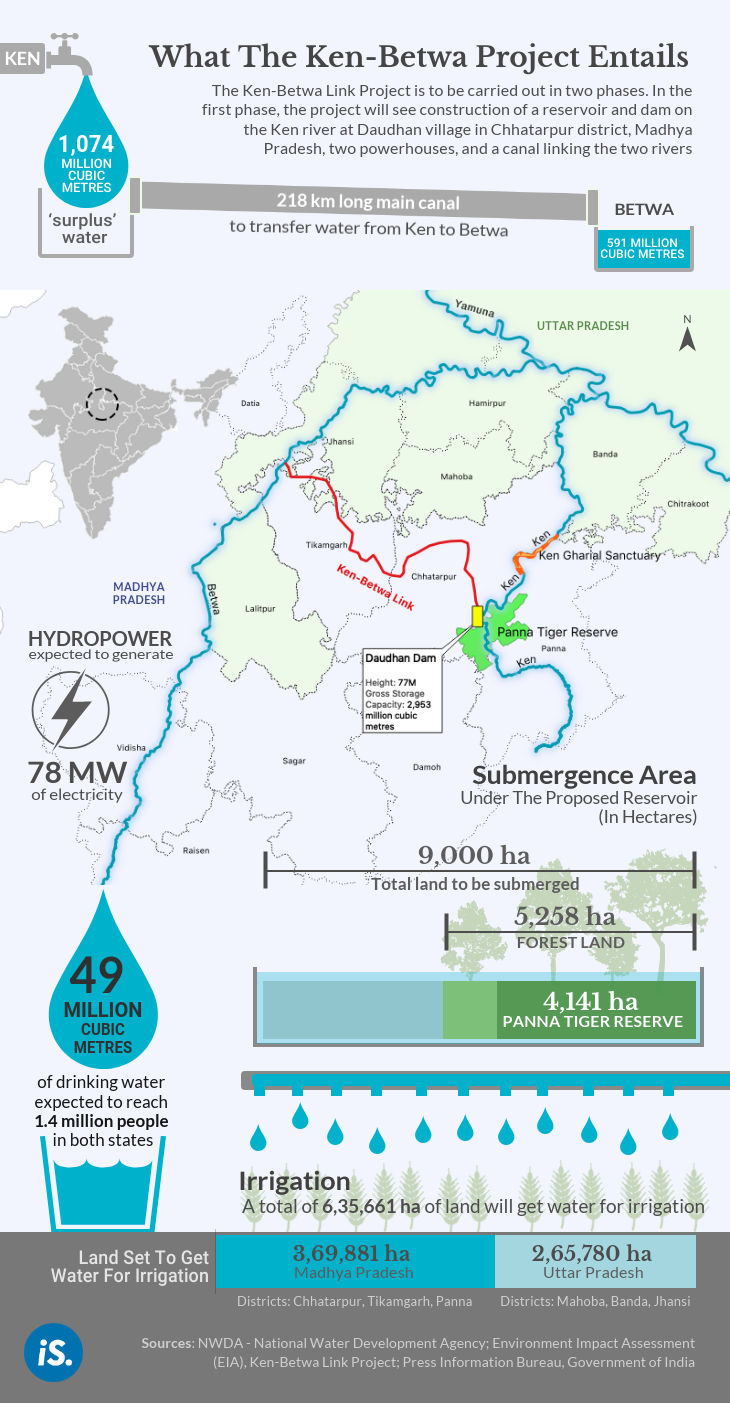

The aim is to transfer the available surplus water from the Ken river in MP to Betwa in UP to irrigate the drought-prone Bundelkhand region, both of which are the offshoots to Yamuna river.

Districts Involved:

Of UP: Jhansi, Banda, Lalitpur and Mahoba

Of MP: Tikamgarh, Panna and Chhatarpur

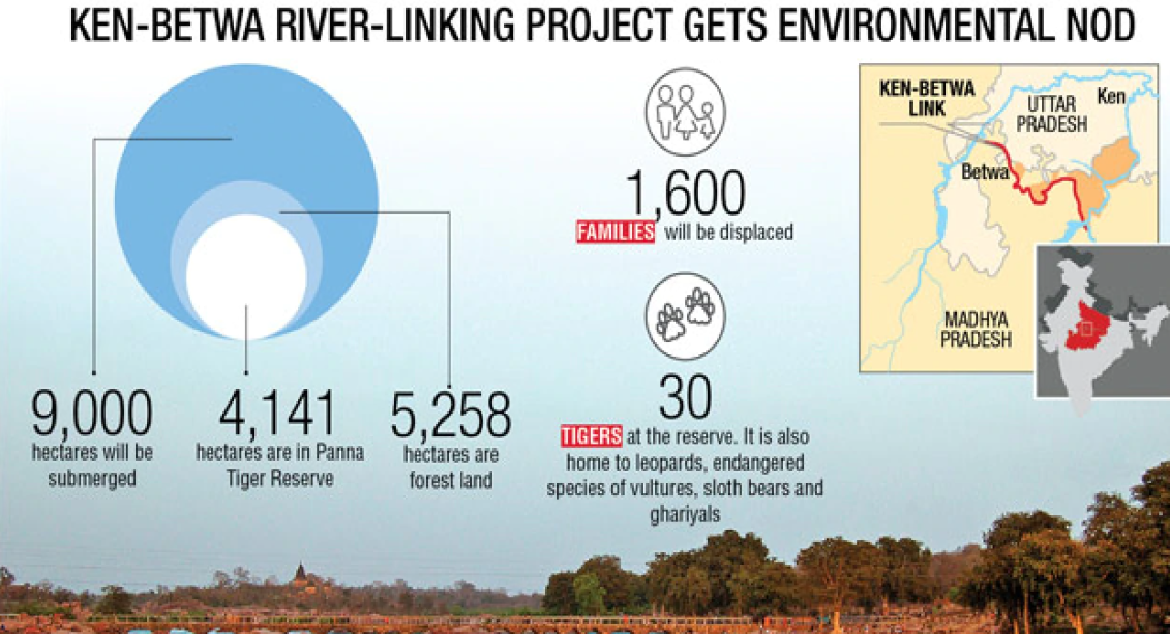

The 280 billion project involves construction of a 77 metre high and 2,031 m long dam across Ken river near village Daudhan in Chhatarpur district of Madhya Pradesh.

Upon completion, it is expected to provide irrigation facility to 606,980 hectares area, drinking water facility for 1.4 million (14 lakh) people and generation of 78-megawatt hydropower.

Controversy around the Ken-Betwa project:

Both the rivers originate in MP and Betwa has held the man-made infrastructure like Rajghat, Paricha and Matatila dams for decades. The problem arises as Ken river passes across Panna tiger reserve, the sole heartland for more than 50 tigers, critically-endangered Gharials and even endangered vultures and following other species:

Leopard, Rusty-spotted cat, sloth bear, wild dog, chausinga (four-horned antelope), mugger crocodile as well as Mahasheer fish, wolves, chinkara, striped hyena, jungle cat, civets, jackal, fox, nilgai, chital, sambar, wild pig, common langur and monkeys.

Threat to Environment:

This project alone will divert 5500 hectares of forest land mostly from the Panna Tiger reserve with nearly 1.8 million trees are to be felled for it. MOEFCC has given the “so-called” wildlife clearance to the project. More than 4,400 hectares of the core of the Panna National Park will seemingly get submerged on the execution of the project.

The impacts on considered species will be long-lasting as they may be prone to noise disturbances, habitat loss etc. during the 9-year tenure of the project.

A frequent trend for forest diversion:

According to a new Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) analysis, there has been 42% rise in such diversion of forestland since 2013 and currently, only 3.5 per cent of the proposed projects have been rejected, else the diversion has been stated non-impacting.

As good as “No Go” lands have even been stripped off and been diverted for other than forest use. ‘No Go’ areas are those having either more than 10 per cent weighted forest cover (WFC) or more than 30 per cent gross forest cover (GFC) under the Forest Conservation Act, 1980.

There is no provision for compensatory afforestation for the fairly-abundant, old-rich trees being sacrificed for the project.

Threat to economy:

The Central Empowered Committee (CEC) of the Supreme Court of India has raised questions about the basic viability and desirability of the project. It has noted that alternatives available to meet the objectives of KBLP have not been examined.

All those provide water conservation/harvesting, even at the local level and that too at a much cheaper cost.

According to CEC, if the hidden costs of implementation of the landscape management plan for tiger conservation and the species recovery programme for vultures and Ghariyal worked out and subsumed into cost-benefit analysis, the project is likely to become economically unviable.

Threat to Biodiversity conservation:

Daudhan Dam could possibly restrict the wildlife corridor in the Panna Tiger Reserve for movement of animals. This will further derail ecosystem functioning there.

During Monsoon, flow of water with silt is essential for the survival of the (Ken) Ghariyal Sanctuary located downstream of proposed Daudhan Dam. Any geographical impediment may isolate the aquatic communities living in upper and lower stretches altogether.

CEC has stressed that the Ken-Betwa project will destroy the most successful tiger reintroduction programme launched in PTR.

Threat to social welfare:

A visible incongruence has prevailed between the information about the river linking in national media and the information available to the communities. The local communities to face the immediate impacts of such change, shall be apprised of the project’s impacts.

According to Mongabay-India, “Most people living in villages along the Ken had absolutely no idea that such a project had been proposed to alter the landscape that they inhabit”.

A few who have come to know, say: “If the water level in the river reduces after the dam is built at Daudhan, then it will mean that our wells will dry up. The two are linked. Essentially, they are stealing our water without ensuring our survival.”

Excerpts from the experts:

Former Environment Minister and Congress leader Jairam Ramesh on March 22 too expressed fear in this regard.

“Destroying old and biodiverse forests to build reservoirs, divert and dam rivers without even appreciating the hydrological contributions of the forest ecosystem, is simply mindlessness,” describes a water expert associated with South Asian Network on Dams Rivers People (SANDRP).

Few ecological experts even dare to deny the whole concept of surplus to deficit water sharing for the project:

Aquatic ecology experts such as Brij Gopal from the Centre for Inland Waters in South Asia (CIWSA) refute that the Ken river has an extra 1,074 million cubic metres of water to share.

He said the NWDA estimates of available water flow in the river are based on observations at Banda, and that these data have not been shared to allow independent verification. Even those sitting on public committees meant to evaluate the project have not seen the data on the Ken river’s “surplus” water.

Instead, the Ministry clarifies: “The data cannot be shared for security purposes since the Ken is a tributary of the Yamuna river, which along with the river Ganga, is an international basin.”

If alternatives are available for a project that is less boisterous but holds greater concerns within its soul, how much feasible is it to continue fetching such a far-fetched dream.

Afterall, Development and Environment are coterminous to each other and not contradictory for Sustainable development is the very heart and soul of larger public welfare.

Also, with climate change at its play, to assert confidently that one basin is going to be permanently surplus ignores the fact that we are already seeing major changes in rainfall patterns and water availability across the country. For instance, change is the only constant for this planet. Maybe we can think forward to change our methods of sustenance, to survive on the crumbling planet.