Do we remember anything about the ones who become runner ups to a prestigious title?

They lose their existence in the limelight. Well, this literally happened for the largest flying bird in the world that lost its fight for the title of the National bird of India.

Hence, the Great Indian Bustard lost this title to the Indian Peacock because of a probability that the country national bird’s name could be misspelt or mispronounced, getting reflected in the wrong light.

But losing the status did not snatch any fame from the bird.

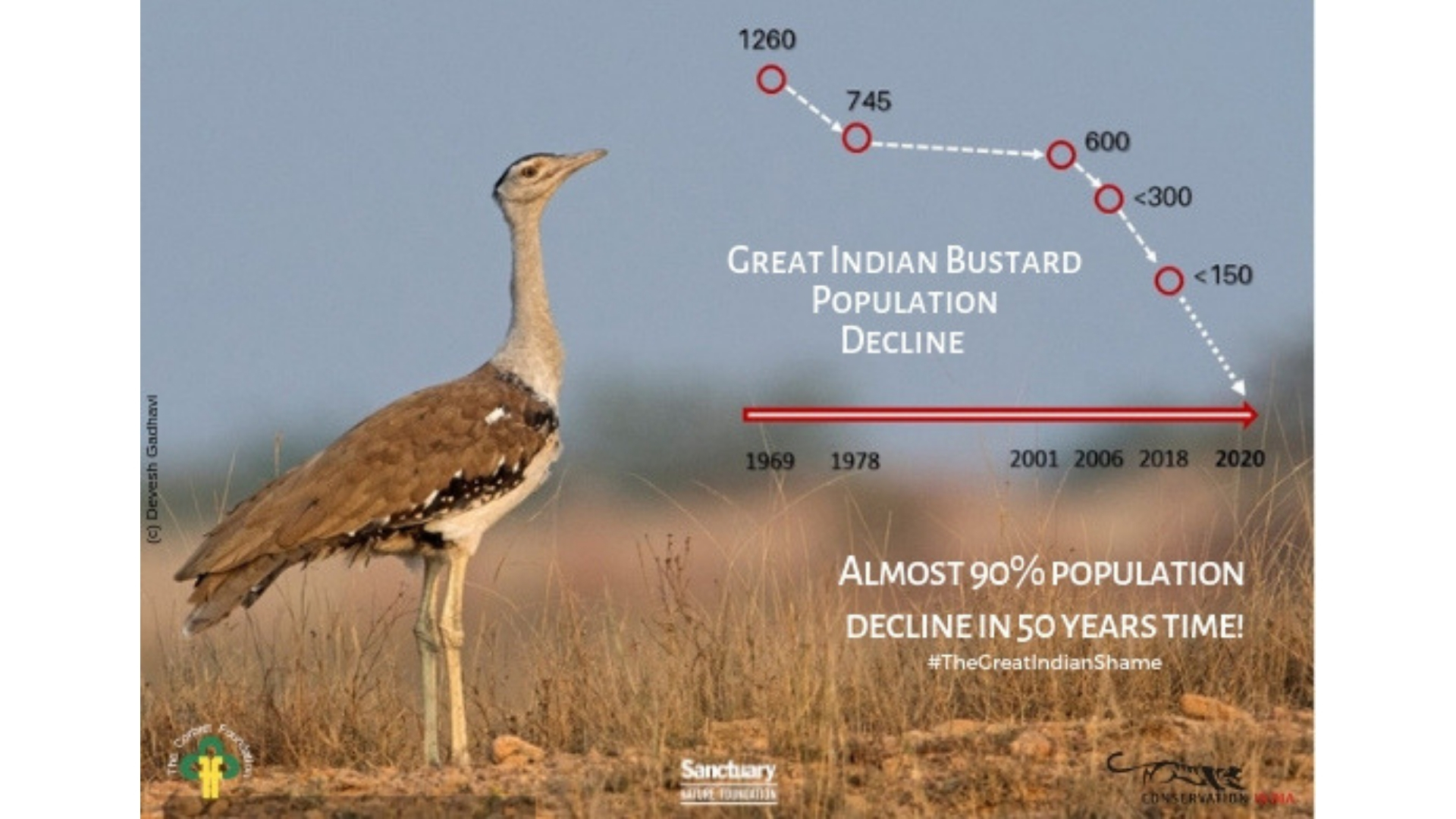

From an estimated 1200 in 1969 to barely 150 in this decade, it lies on the brink of extinction and is a constant subject of worry for ecologists and researchers.

Prominently i.e. around 120 individuals are only found in the districts of Barmer and Jaisalmer (Desert National Park, Rajasthan) and Gujarat, except scarce populations surviving in Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka.

For a considerable time, even the local community did almost nothing to help in conservation efforts of GIB and despised any such attempt by the forest department too, before realizing the fast-moving trail of death.

The Chief Conservator of Forests explains: “When it comes to protecting an endangered or critically endangered species, the state alone cannot do everything. True, there are laws like the Wildlife Protection Act 1972 in place but even for implementation of the laws, we need support (of the community)”.

Thereafter, the local community has been carefully educated and their contribution now stands crucial to conserve GIBs and their natural habitat i.e., the dry grasslands or scrubs we have dared to consider as wastelands.

A local guide adds: “The training gave us a lot of information about birds and with experience over these last few years, I have learnt even more”.

A passionate protector of GIBs claims: “We believe that the GIB and its habitat can be saved only if the local community supports it. And I am happy that they are responding positively to it.”

The best that can happen to these lands, as per human greed, is their diversion to either cultivation, solar or windmill infrastructure placement or construction.

This has collectively led to their doom. Their biggest enemy is the overhead power lines that entangle them as they take their flight.

If we are to believe the Wildlife Institute of India (WII), an estimated 18 GIBs die every single year because of collision with power lines.

In this regard, even the mighty Supreme Court has directed the governments of Gujrat and Rajasthan to install bird-diverters on these overhead power cables or simply get them underground.

While humans may have changed their functioning towards these beings, in a similar manner, even the bustards have altered their ways of innate survival.

In the last 40 years, the GIBs have restricted their own movement to certain smaller parts of the Desert National Park.

Does Climate Change have something to offer to the Great Indian Bustards?

Based on certain speculations, climate change might have changed the rainfall pattern in last few years in arid and semi-arid regions of India, that leads to flooding.

For the area concerned, ‘heavy rainfall’ pertains to receiving 65 millimeters per day. Eastern, western and southern parts of Rajasthan have been experiencing the same almost every year.

This will only increase in future, as per the data observed by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation.

But the changing pattern of rainfall has ushered in good tidings for this bird enduring losses. The primary fodder for the bird called sewan grass has been recorded to have increased post floods besides the affinity for small reptiles, grasshoppers, insects or locusts.

Moreover, the bird has also changed its egg-laying customs, believed to be an outcome of a better nutritious diet consumed, as an outcome.

Environmentalists and ornithologists relevant to the cause of saving GIBs have upheld this new habit as now the bird lays a clutch of two eggs for the same period of time it used to lay only a single egg.

An expert explains: “The natural feed for birds gets produced in abundance whenever it rains excessively in the DNP”.

The incidence was first observed in a few during 2020 monsoons but a repetition of the same indicates an evolving habit.

As per the inputs from Wildlife Institute of India, six nests in the Desert National Park each with two eggs in it have been discovered so far.

This egg-laying conundrum came to the fore back in the 1980s during an international symposium on bustards held in Jaipur. Most of the experts present swore to the fact of GIBs laying only one egg a year but our very own inspirational Salim Ali opined the bird to have laid more than an egg in certain cases.

A human cannot fathom the vagaries of nature in a single scenario. While changing weather patterns may have troubled us humans, they seem to have become blessings in a few cases.