With decreasing resources on this planet, we call home and increasing expectations, there has to be competition for every other thing to survive.

Even to attain sustainability in the long run, there shall be multiple ways to get the task done, yet one is supposed to choose the best and most efficient method out.

With significant time, we have learnt to combine a class of things to get all the great things done. For instance, a piece of arid land with bare vegetation and providing no source of subsistence to any, can be turned useful.

It can turn into a countable asset if solar power generator, wind energy generator and even a grassland is found to thrive a mini ecosystem.

The land of conflicting interests: Bustards v/s Renewable Infrastructure

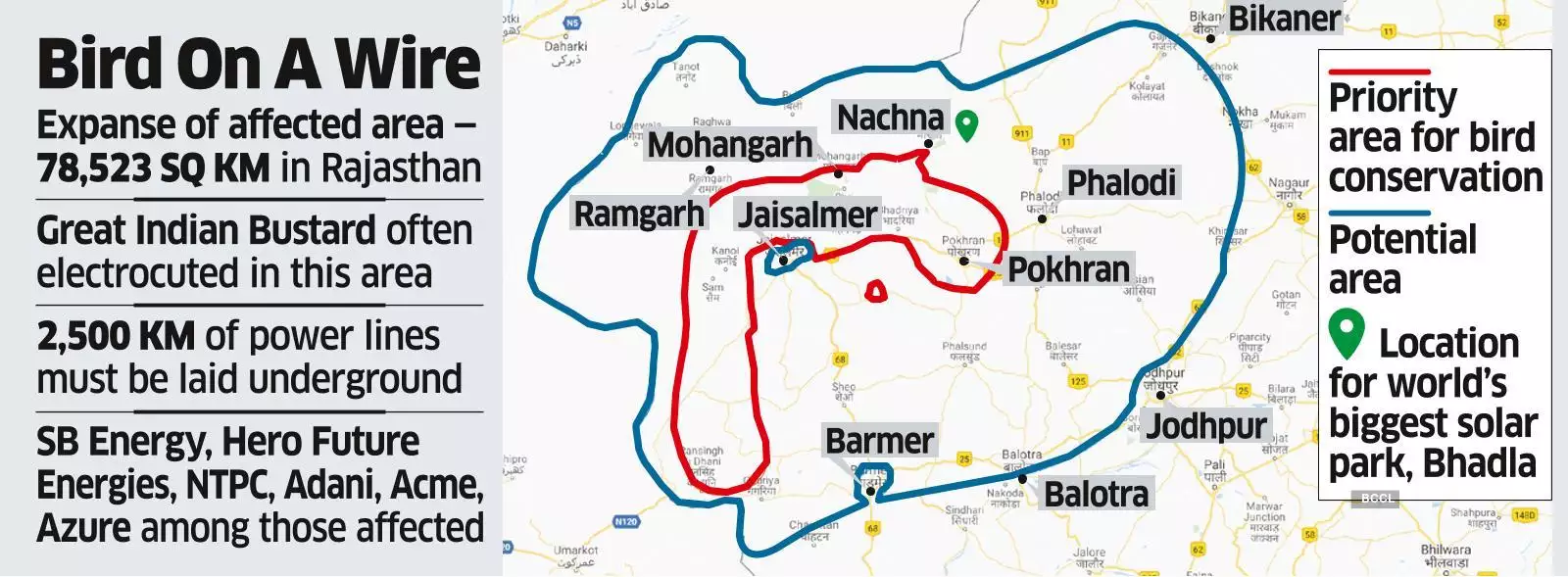

With more than 90% of its population decline, total Great Indian Bustards (GIBs) are estimated to be 150 across Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh.

The India’s national bird, lying on the brink of extinction, are “in the greatest need of protection” because of public apathy or “direct human persecution”, as per the famous Ornithologist Salim Ali.

But one of the major reasons killing them in huge numbers, is the poor frontal vision they have and the incapability to take higher flights because of bulky size which often results in mortality due to collision with electricity transmission lines.

Concerted efforts have been made in this direction, from the Wildlife department undertaking the wire-fenced enclosures to save the grasslands, their habitats or ‘No’ permission to the NHAI project by concerned governments.

Or simply the Supreme Court’s priority measure of getting the Diverters installed along the major GIB routes with High Tension Lines or getting the low Voltage transmission lines underground.

Due to collisions with these powerlines alone, nearly 10-18 of these majestic birds die every year.

This high rate of mortality can possibly accelerate the rate of extinction of GIBs as they remain only lesser than 150 in numbers.

Cropping out of the petition filed by various Environmentalists, all this was to be done within a year.

But as the judgment intended to ensure survival of this endangered species, it has fallen short to address some of the practical problems for developers undertaking Solar projects in the region.

“In the recent past, we have seen that Supreme Court has entertained review petitions filed by the government.”

The existence and operations of 65 GW of solar and wind energy projects seems difficult as these lie in the priority and potential habitats of the birds in Rajasthan as well as Gujarat.

“In this matter as well, if the government can give a solution balancing the need to protect the endangered bird species and uphold the interests of the renewable energy assets, the Supreme Court may modify its orders.”

What did Wildlife Institute of India say in this regard?

WII published a report by the name ‘Powerline Mitigation, 2018,’ that stated how 100,000 birds of different species die due to collision with powerlines every year.

WII has said clearly: “Unless powerline mortality was mitigated, extinction of the Great Indian Bustard was inevitable”.

Why the previous judgement has not been embraced in all regards?

Though saving lives is an urgent call with highest priority, yet there needs to be a proper balance between harboring safety and fulfilling the developmental needs of a region, especially when it is sourced from Renewables.

Consequently, in its response, Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) filed a response: “In case, undergrounding of lines is insisted upon, India might need more fossil fuel-based conventional sources to meet the shortfall of renewable energy.”

“This will end up increasing our carbon footprint, which will be detrimental for the environment”.

As per the experts from Renewable sector: “All the ongoing projects are stuck, and the transmission line approvals are not going through. And without the transmission line, the project construction cannot make progress.”

This happens because the underground/insulated cables for 765 kV are not manufactured in the whole world. In case of 400 KV lines, the maximum length for an underground operation can be 5 to 8 km only.

From the geographical perspective: “The impact is not that great in Gujarat’s Kutch region. It is basically affecting the projects in Rajasthan, which is why the Solar Energy Corporation of India’s (SECI) tender is not going through.”

As per a few estimates, shifting the mesh of powerlines deep underground may render a final expenditure of ₹1.5 trillion (~$20.15 billion).

For laying a 33 kV cable underground, the cost is around ₹3-5 million/km, for a 132 kV cable, it is about ₹18 million/km, for a 220 kV line about ₹70-100 million/km and for a 400 kV underground line, the cost in averaged to be around ₹120-150 million/km.

The question remains how the Supreme Court hopes to strike a balance so as to help save the birds’ dwindling existence and also that of the renewable power in India.