Time and again, India has re-assured the world of its intention to contribute in curbing global emissions and provide a meaningful pathway to climate action.

Recently, the country has passed its Energy Conservation (Amendment) Bill 2022, which has been crafted to incentivize actions for emission control and reduction that will further prepare ground for increased investments flowing in clean energy by the private sector.

The Ministry made a statement: “It is forward looking, it is futuristic. We are keeping up with the world. In fact, we are leading the world.”

The message is clear and loud, at least for those who seek it.

Phase-down is what we know we need:

While COP 27 in Egypt could draw out nothing conclusive, it has been apparent twice and more that the world is now progressing towards a ‘phase-down’ of coal i.e., lowering down the usage of coal over a period of time in a controlled manner and not a complete ‘phase-out’.

India has been one of the biggest proponents of this gameplay, alongside extending the phase-down scenario to not just coal but also other fossil fuels.

Why did India embrace this option?

Amongst various shared reasons, India had a few prominent reasons to call its own.

Although the country has promised to achieve net-zero by 2070, the phasing-down of fossils requires no timeline for the realization of its goal.

In simple words, phase-down for any developing country including India means to possess and use its own finite pool of fuel resources, generally the non-renewable ones like coal to meet the increasing energy demands but without constraining it to a timeline ending the usage of fossil fuel.

The phase down is intended to give some buffer to currently commissioned coal-based power plants which may have a remaining life cycle of 20 or 30 years.

Despite the efforts to source India’s 50 percent energy from the renewables, the country still has about 200 GW installed capacity based on coal i.e., nearly 80 percent of the country’s energy needs are sourced from the fossil fuels.

It is expected that a staggering 1.5 billion tonnes of coal will be crucially needed by 2030 to accelerate the existing gears of growth this developing country demands.

Because of the green-promoting endeavors, coal-lined projects are continuing to face difficulty in terms of finance; a linear phase-down will only provide some umbrella assurance to such projects’ investors.

Most of these are domestic sponsors only and big Indian coal players have recently been staying away already from these auctions.

One may wonder why this scaling down of an ‘urgent calling’ was needed? When the planet is experiencing jolts from all its corners and humankind has turned clueless in understanding most of its twisted mechanisms, can this simple step belittle all our future plans?

Well, with Nature ready to reciprocate for our past wrongdoings and a vulnerable humankind on the other side, it becomes difficult to pick a side.

With grave scientific data and research pertaining to ever-increasing climate studies, one can ascertain why this delay, not apparently a collective good, may be better for many lives and livelihoods in the country.

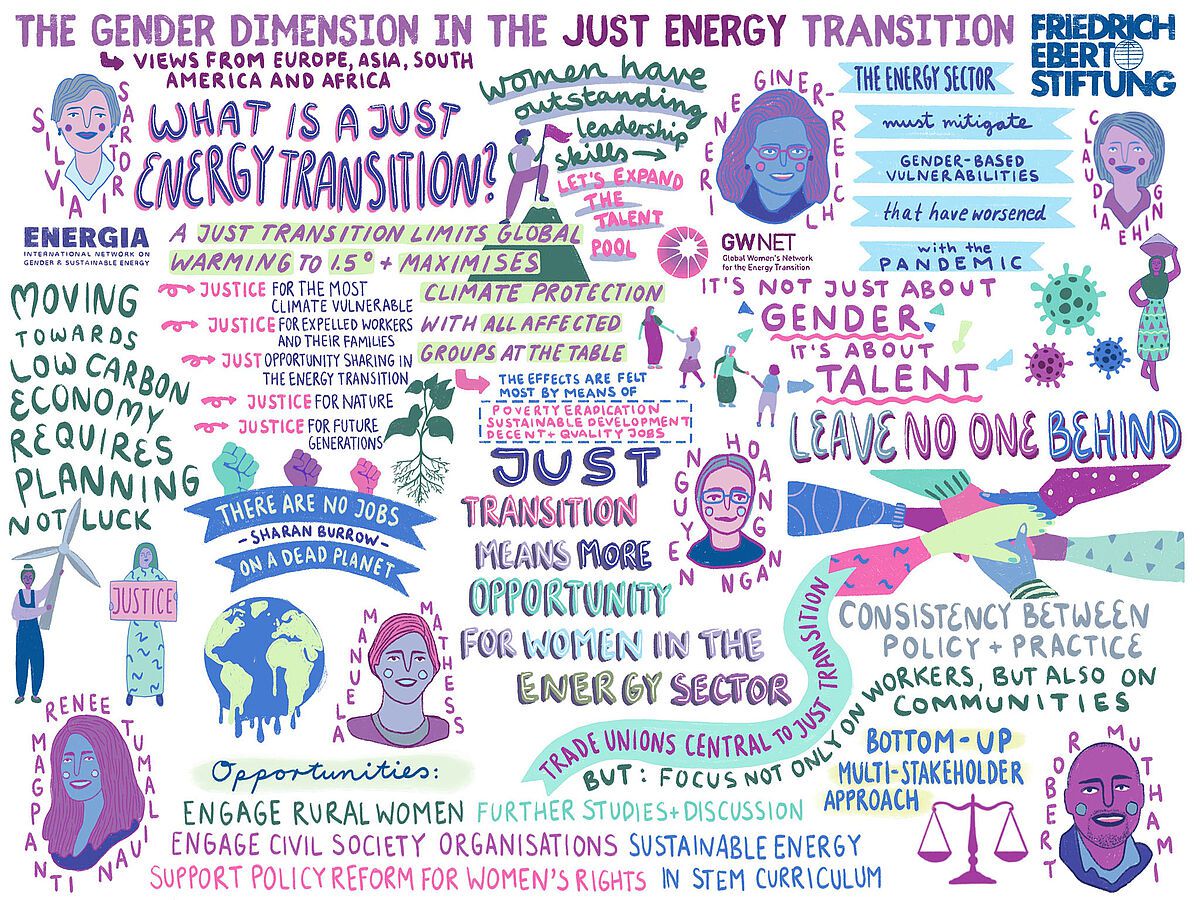

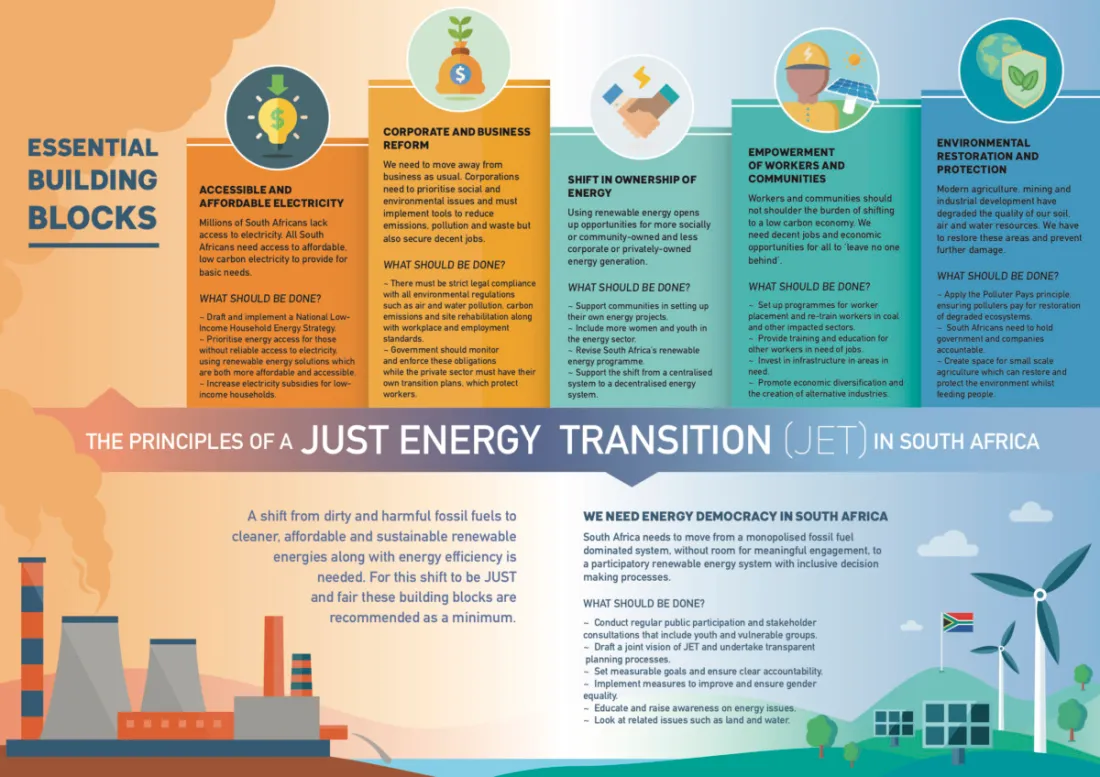

Energy Justice: Fuel, demography and decarbonization

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates have projected the renewables to supply nearly 70- 85 percent of electricity in a 1.5 degrees C scenario-based 2050, and the share of coal will be close to 0 percent of energy generation.

There are decent findings suggesting that an unchecked, irresponsible and above all, non-inclusive energy transition could prove to be more disruptive to our demographic entities than the removal of coal.

A minimum of 33.5 million people, and an additionally possible 115.7 million people will be affected severely in case all the transition projects begin their production.

However, the impacts are rather region or country-specific and are limited by their own barriers against implementation, such as the quantum of economic dependency on dirty fuels, geopolitical concerns etc.

For instance, in mining-driven towns, impacts of a rapid transition may be deadly though a just energy transition may have its own impacts too.

This happens because the mining projects remain lifelines of economic activity and consequent growth in these areas, allowing not only nearby available labour sustain but also shopkeepers, local agents, tea-stalls etc.

And hence, this mine-town symbiosis generates socio-economic assets and strengthens its functions, in and out.

A Researcher has cleverly pointed out in his study over mine-town demography: “As with trophic levels in a food web, mining projects represent producers and towns represent consumers. Supply interactions across the system are bi-directional, providing functions that feed population demand and a population that in turn feeds the functions.”

An unplanned and unjust mine closure can lead to significant job losses, displacement and migration, infrastructural degradation, lack of essential services and subsequent ripping of social structures.

According to an estimate published by journal nature, nearabout 1.92 lakh formal plus informal workers would experience unemployment by 2030.

With emigration happening from these small yet sustaining towns and cities, there will be a burden shift somewhere else. Putting the exiting abundant resources to ultimate use will prove to be a daunting task.

Wherein, the task of diversifying economy, utilizing the industrial factors of production can become lengthy, distraught and expensive mechanism.

Socially, this can lead to resentment, hostility within groups and even populism.

“Any unplanned closure of mines has major negative implications on environment, land degradation, local economy, and social stability. A well-planned and managed transition of such mines can be win-win for the industry, workers, affected communities and the environment,” explains an expert from the iForest organization.

Secondly, the opportunity cost has gone higher.

Because when a coal plant is decommissioned and in place of it, a solar or other renewable energy plan is set up, it is not done in the same region.

Similar is the scenario, even for afforestation efforts that the area devoid of trees by cutting is not provided with the other set of trees, not even closer.

Therefore, renewable energy plants are normally setup in other easy areas like Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Rajasthan etc. which have no truck with the dirtier resource, while the mines get shut down in regions around Chhota Nagpur.

Isn’t that unfair to the communities dependent on coal economy, they get no deserving recourse!

Most important of all, while the just transition debates are in plenty elsewhere and in the country, but India has formulated no legal guidelines on how this will this change take place like how will the coal mines be disposed of, what will happen and who will own 100,000 hectares of the land with such mines in the country, will mine closure have environmental impact assessment as well etc.

In the words of a field expert: “Considering the multi-faceted issues related to coal mine closure under the principles of a just transition, the current laws and regulatory mechanisms remain inadequate, and require reform measures to be undertaken to facilitate a just closure and transition process.”

Certain unofficial calculations have chalked out around 1,100 billion to be required for retiring India’s total coal-based capacity. However, there is no such word of funds being kept aside by the power plant owners.

Also, thermal power plants based on coal are known to emit and release toxins like fly ash, polychlorinated biphenyl, mercury or lead. There are no legal facets for this possible hazard.

The world experienced what it is like to linger in an energy crisis. Experts suggest that on the way to Energy transition, there will be many more to come and hit economies already debilitated by the pandemic.

Are our plans to replace the dirtier fuels potent enough?

A similar Conundrum:

As revealed in the data collected in a developed country like the US, nearly 93 percent of coal-dependent rural towns (1262) have no other alternative post closure, to utilize their resource pool.

Experts say that without any adaptation plan in place, innovative solutions, effective governance measures and attention to public issues, severe economic hardship coupled with social distress to millions of lives associated with coal specifically.

This black jewel has caused enough distress to this planet and its beings; however, its withdrawal shall be made a little easier.