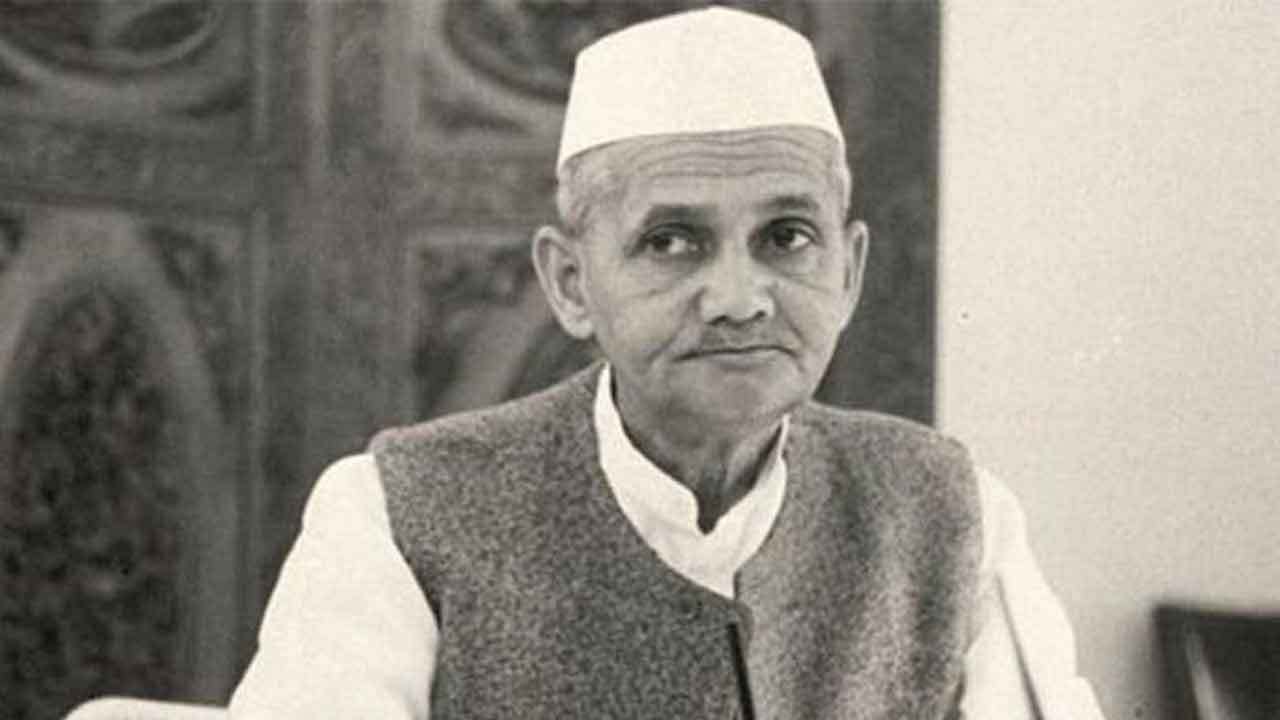

Lal Bahadur Shastri was a senior leader of the Indian National Congress, a key figure in the Indian Independence movement, and India’s second Prime Minister. He succeeded Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru in 1964, after the latter’s sudden demise. He is remembered for leading India though the Indo-Pakistan War in 1965, being relatively new to the high office. He realised the need for self-sustenance and self-reliance in India, and raised the slogan ‘Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan’ which he is remembered for even today.

Lal Bahadur was born in Mughalsarai, United Provinces (Modern day Uttar Pradesh). His interest in the freedom movement had its inception in high school, under the tutelage of his intense and highly patriotic teacher Nishkameshwar Prasad Mishra. During this period, he began to extensively read the works of Swami Vivekananda, Gandhi and Annie Besant. It was around the same time, in January 1921, when he attended a public meeting in Banaras (Varanasi) organised by Gandhi and Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya. Shastri withdrew from Harish Chandra High School and joined the local branch of the Congress party as a volunteer, after Gandhi’s call for withdrawal from government schools as part of the ‘Non-Cooperation Movement’.

Shastri was one of the first students of Kashi Vidhyapith, a ‘nationalist education’ school started by J.B. Kripalani (A close follower of Gandhi) and V.N. Sharma. Shastri graduated with a first-class degree in philosophy and ethics from the Vidhyapath in 1925, where he was given the ‘Shastri’ (Scholar) title. He adopted this title has the suffix to his name, long after he dropped his caste-derived surname of ‘Srivastava‘, thus becoming Lal Bahadur Shastri.

Under the instructions of Gandhi, Shastri worked for the upliftment of Harijans in Muzaffarpur, after enrolling himself into the Servants of the People Society (Lok Sevak Mandal) started by Lala Lajpat Rai. He later served as the President of the society.

By 1928, Lal Bahadur Shastri was one of the most important figures of the Congress at the behest of Gandhi. He participated in the ‘Salt Satyagraha’ movement or the ‘Dandi March’ in 1930, for which he was arrested and imprisoned for two and a half years. in 1940, he was arrested again for offering individual ‘Satyagraha’ support to the freedom movement.

Following his release, Shastri traveled to Allahabad where he began sending instructions to freedom activists from Anand Bhavan (Nehru’s home, at the time) which were part of Gandhi’s ‘Quit India Movement’. He was subsequently arrested, and imprisoned until 1946.

Following India’s independence, Lal Bahadur Shastri was appointed as the Parliamentary Secretary of Uttar Pradesh. Under Chief Minister Govind Ballabh Pant‘s leadership, he was appointed as Minister of Police and Transport on 15th August 1947.

He was the first minister to appoint female conductors as Transport Minister. As Minister in charge for the police department, he instructed authorities to use water-jets instead of ‘lathis’ to disburse unruly crowds. He was successful in mitigating the communal riots of 1947, as a result of mass immigration and also oversaw the re-settlement of refugees from the newly formed Pakistan.

In 1951, Prime Minister Nehru appointed Shastri as General Secretary of the All India Congress Committee. In May 1952, Shastri was appointed as the Railways Minister as part of the First Cabinet of the Republic of India.

Following Jawaharlal Nehru’s death on May 26th 1964, Shastri was appointed as his successor on June 9th in the same year. His Prime Ministership came as a result of the efforts of the then Congress party chief Minister K. Kamaraj.

Though mild-mannered and soft-spoken, Shastri was a ‘Nehruvian-socialist’ who is remembered for his calm demeanour even in the most dire of situations.

Here is a list of the major achievements of Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri.

Contents

I. Appeasement of Non-Hindi speaking States

During the Indian Freedom Struggle, there was mass mobilisation under the leadership of Gandhi for the replacement of the English language to Hindi and regional languages. The intention behind this was to bridge the gap between the elite class and the common folk, in a bid to associate them towards constructive works in nation building.

The Nehru report supported the making of ‘Hindustani‘ as the official language of India, in a bid to give encouragement to provincial languages. However, as English was used in all official correspondences by the leaders, it couldn’t be gotten rid of. Moreover, little attention was paid to the details of the vernacular language notion, in terms of how the choice of the national language would affect North-South states’ relations.

Though voices and protests against Hindi were observed in different parts of the country, it was Madras that vehemently voiced its opposition to the notion. An Anti-Hindi Conference was held on January 17th 1965, and was attended by D.M.K. leaders and C. Rajagopalachari.

The conference deeply criticised the ‘language policy of the Union government’ and expressed a firm determination of the people to resist the imposition of Hindi. Students organised widespread Anti-Hindi agitations in Madras and Madurai, where the agitations took a violent turn and went on for two months.

Students in Madras were able to compete better in the All Indian Administrative Service with their proficiency in English, and feared losing their lead in the service as a result of the imposition.

Lal Bahadur Shastri, though initially reluctant to translate Nehru’s assurances to Non-Hindi states that ‘no switch over to Hindi would take place until they were ready for it’, following the agitations in Madras; gave assurances to these states that English would remain as the official language. Following this, the agitations died down.

II. White Revolution

A significant section of India’s population are largely agrarian, with dependencies on agricultural produce and cattle milk production for their livelihoods. The milk industry, according to Dr. Verghese Kurian, is the only industry that allows a marginalised family to earn a small amount of cash everyday; requiring a small amount of investment in purchasing a milch cow, and providing nutritional supplement to the children of the house.

According to Kurien, the absence of an efficient collection and distribution system for milk, were reasons for the marginalisation of cattle owners.

Under the leadership of Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri, Dr. Kurien set up the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) and the Gujarat Co-operative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF) or the Amul Dairy Co-operation, in 1965.

The White Revolution eventually gave rise to ‘Operation Flood‘, a project by NDDB, which became the world’s largest dairy development program. It transformed India from a milk-deficient nation to the world’s largest producer of milk, surpassing USA in 1998. In 30 years, the milk production per person doubled making dairy farming India’s largest self-sustainable rural employment generator. As of 2010-2011, India accounted for 17% of the global output in milk production.

III. Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan – Green Revolution

The British Raj in India saw the nation being reduced from a net exporter of food to a net importer in 1919. Moreover, the food shortages in the Bengal Famine of 1943 caused the estimated deaths of between 1.5 to 3 million people due to starvation. Following the partition of India by the British, Punjab was split between both the nations. Punjab is the wheat growing centre of India, but following partition; most of the irrigated croplands went to Pakistan along with a majority of India’s agricultural research and education facilities, including the ‘Agriculture College and Research Institute at Lyallpur’.

Food shortage was one of the biggest problems for India, following the exit of colonial rulers. Lal Bahadur Shastri’s tenure as PM was characterised by acute food shortages, with imports of food touching 10 million tonnes which helped avoid a famine. He appealed for a one-day fast every week to reduce the demand for food.

At the time that Shastri ascended to the role of Prime Minister, India was attacked by Pakistan. This period, as mentioned earlier, saw a scarcity in food grain production in the country. He raised the slogan ‘Jai Kisan, Jai Jawan’ (Hail the Soldier, Hail the Farmer) slogan in a big to boost the morale of the Indian Army, and to encourage the farmers to do their best to increase food production of grains for reducing imports.

At the time of his Prime Ministership, C. Subramaniam was the elected Minister of Food and Agriculture. Subramaniam and Shastri worked together to increase food production via increased government support. Taking recommendation of the Foodgrains Prices Committee offer incentive prices for grains that are higher than procurement and market costs. Subramaniam also favoured increasing government reserves of grains buy purchasing them in the open market on incentive prices.

Subramaniam published the ‘Agricultural Production in the Fourth Five-Year Plan: Strategy and Plan’ in 1965, which marked the government’s commitment towards the ensuing Green Revolution.

IV. Sirima-Shastra Pact

The Sirima-Shastri Pact was bilateral agreement signed between India and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) which focused on the citizenship of Indian workers in Ceylon. The pact was signed by Ceylon’s Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike and Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri on October 30th, 1964.

The issue at hand went back to pthe re-independence colonial rule where, in 1833, the Colebrook Reforms brought several changes to the island’s socio-economic structure. These reforms abolished the trade monopolies of the government, by paving the way for a capitalistic system characterised by private enterprise.

The introduction of the Waste Land Ordinance in 1840 saw the occupation of large quantities of unused land, and selling them to newly arriving classes of private planters and entrepreneurs. The British then authorised the large-scale establishment of commercial plantation leading to the arrival of South-Indian workers.

They were brought because they were willing to provide labour services for cheap payments, and they were familiar with the cultivation of Tea. Moreover, the local Sinhalese refused to be employed in plantations.

The Island-nation gained its independence in 1948, where the citizenships of these Indian workers were questioned. The Citizenship Act of 1949 stripped the legal citizen statuses of the Indian workers. A series of unsuccessful negotiations led Mrs. Bandarnaike to visit in India in 1964, and the pact was drafted after six days of negotiations.

The objectives of this pact was to recognise all people of Indian-origin in Ceylon who weren’t citizens of either India or Ceylon; should become citizens of either India or Ceylon. The Indian government would accept repatriations of persons within a period of 15 days. Ceylon agreed to allow those people who were employed during the signing of this pact, to continue with their jobs until the date of their repatriation.

V. Repatriation of Indians from Burma

Between 1948 and 1962, Burma (Myanmar) had a democratic, Parliamentary government. It was, however, plagued with widespread conflict and internal struggle. The political and ethnic tensions weakened the Burmese government, following constitutional disputes as well. By 1958, the Prime Minister of Burma, U Nu was forced to accept military rule, under the interim rule of General Ne Win, to restore political order. The military eventually stepped down after 18 months, but there were gaping holes in U Nu’s government which left it vulnerable for rivals to exploit weaknesses.

On March 2nd, 1962, a military coup d’état was staged by General Ne Win, thereby negating the constitutional and democratic government, and establishing military rule.

Under the military rule, many Indians who had been assimilated into the Burmese culture for centuries becomes targets for oppression and discrimination by the people and the government. General Ne Win ordered the large-scale expulsion of Indians from Burma.

The Central government monitored all the processes of repatriation and arranged for the identification and transport of Indians from Burma. Local governments were asked to providee adequate facilities to repatriates upon disembarking on Indian soil.

In December 1965, Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri made an official visit to Rangoon in Burma, along with his family, and re-established cordial relations with the military government of General Ne Win in Burma.

VII. Indo-Pakistan War and Tashkent Agreement

The Indo-Pakistan War of 1965 highlighted one of Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri’s greatest moments as leader of the nation. The war was initiatied when Pakistan laid claim to half of the Kutch Peninsular in a skirmish against the Indian Army.

Shastri said that, while India had no intentions of causing trouble with its bordering neighbours, and that the country’s focus of utilising its limited resources was for the economic progress; under the possibility of an incursion, the government would be quite clear in its objective of protecting the nation, and its duty in this regard would be wilfully and uncompromisingly discharged.

“We would prefer to live in poverty for as long as necessary but we shall not allow our freedom to be subverted.”, Shastri said, in his report to the Lok Sabha.

The war with Pakistan went on for 5 months, between April and September of 1965, and resulted in around casualties of about 3000 to 4000 people on both sides.

On September 23rd, 1965, the United Nations mandated a ceasefire resulting with the war ending between India and Pakistan. After the declaration of the ceasefire with Pakistan in 1965, Prime Minister Shastri and the then President of Pakistan, Ayub Khan, entered an agreement in Tashkent (formerly of USSR, now part of Uzbekistan), mediated by Premier Alexei Kosygin.

The Tashkent Declaration was signed between India and Pakistan on January 10th 1966- to give away the conquered regions of each other by both parties, and return to the 1949 ceasefire line in Kashmir.

Conclusion

Lal Bahadur Shastri has an extensive history of being a freedom fighter, nationalist, and leader of the nation. He was primarily concerned with the basic economic problems of the country at that point of time- food shortage, poverty and unemployment.

Incidentally, he shares his birthday with Mahatma Gandhi on October 2nd.

Shastri’s death remains a mystery, though officially reported as a heart attack, a after signing the Tashkent Agreement on January 11th, 1966.

He was the first person to posthumously be awarded the Bharat Ratna, India’s most prestigious civilian award.